City’s Transformation in 20th Century

Bratislava Goes Post-Industrial

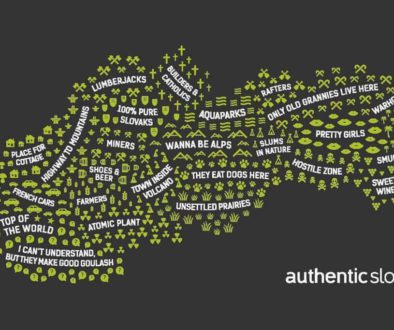

Have you ever heard of Manchester in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire? – Probably not, because Manchester is and always has been in England. However, this nickname was sometimes used to describe Bratislava by the late 19th and early 20th century because of its rapidly booming industry. However, transformation of Bratislava since then has been significant.

Once a medieval fishing town and later capital and coronation city of the Hungarian Kingdom, it suddenly changed its silhouette and the number of chimneys soon exceeded the number of church towers.

The year 1848 is known as the revolutionary year in many parts of Europe. A series of revolts that also struck Slovakia as part of the old fashioned Hungarian kingdom were unmistakably a sign of a transition from feudalism to capitalism – the new era in which capital becomes dominant. Businessmen and factory owners formed a new cast which was able to accumulate wealth without belonging to the nobility or church. These wealthy people in exchange provide opportunities for the workers and contributed to the industrialisation and growth of cities.

1848 can also be viewed as the milestone marking the industrial revolution in Bratislava. In this year the railway between Bratislava and Vienna was established and the train service, operated by modern steam locomotive between these two cities, began and remains on the same route until this day. This railroad includes original bridges and viaducts from 1848, as well as the first railway tunnel excavated in the former Hungarian monarchy of the same year. It was clear at the time that the traditional animal power of horses was already becoming outdated. Just few years after steam locomotives replaced horses in 1840 on the railway line between The line from Bratislava to Trnava held the record as the very first railway in the monarchy. Horse-train station with its Big Ben like tower is still standing as a unique memorial of this era at the corner of Legionarska Street.

Good and modern connections with other parts of the monarchy and rest of Europe were necessary for the upcoming industrialisation. Therefore, the first big factories were founded and began to grow near transport hubs such as Danube harbour and railways.

Chemical production has always been among the most important industries in Bratislava. The big and modern Apollo oil refinery started processing the black gold as soon as 1895. It took up the area between Panorama City and Apollo Bridge named after the refinery as a tribute to as many as 200 employees who perished in the bombing of 1944. The refinery and other factories were chosen by the allies as strategic targets which had supported the Nazi war machine.

Another very important chemical plant was the dynamite factory founded personally by the inventor of dynamite Alfred Nobel. Entire housing colonies for workers together with the factory were built. During communist times the factory was renamed for ideological reasons to the Georgi Dimitrov Chemical Plant. He was the leader of the communist revolution in Bulgaria. At its peak then Dimitrov factory employed more than 7000 people and became by far the biggest employer in Bratislava. After the Velvet Revolution the factory was again renamed to the more neutral name of Istrochem. Today, it has only a handful of employees and most parts of it are slowly turning into ruins and has become an attraction for urban explorers. Since the plants decline, the air quality in Bratislava has become much improved, but the area of 120 hectares, which it covers, remains highly polluted and is one of the biggest environmental issues of the city at present.

Currently however, in contrast to the demise of Istrochem, numerous factories in Bratislava make products for daily use, an example being the textile industry. Textile production has belonged amongst the most prominent industries in Bratislava, since the very early 20th century. One of these factories, very well preserved but with an uncertain future, is called by locals the ‘Pink Castle’ and it`s located near Trnavske Myto. It is a wonderfully decorated and very functionally built factory building with a shape similar to Bratislava Castle and has a pink painted facade, hence the nickname.

Today, Bratislava is also a popular destination for those who come to enjoy the cheap but good beer in many pubs in the old town. However, not many of them have any clue about the once very famous brewery – Stein, which actually became the 3rd largest brewery in Czechoslovakia after Pilsner and Budweiser in 1970`s. In 2007 after almost 140 years production was stopped and the brewery had to make room for a new housing project with unimaginative name „Stein2”. Thus, not only a loss for beer lovers, but one of the symbols of Bratislava was permanently gone, lost to posterity. As a compromise between reckless development and preserving valuable industrial heritage, the most notable part of the Stein brewery building, the dome-like roof, will be incorporated in the new project.

Nowadays, there are still some traces of the industrial identity of this city visible but unfortunately some of the most remarkable pieces of architecture are forever gone. But how is this possible? Isn`t a renovation of an old factory and its transformation into a fancy loft housing or extraordinary hotel something that we would normally expect in the 21st century?

Apparently not, in Bratislava we have been witness to a recent large scale destruction of the industrial footprint and once again, as we saw in history, it has forced a new identity onto the city. Valuable architecture that somehow survived the 1944 bombing and 40 years of Communism is now being turned into dust and memories because we need more cheap office buildings for big corporations and blocks of apartments with often questionable quality and aesthetics. They are not so different from the infamous prefabs built by the communists. I hope that this rather pessimistic conclusion will serve as a wake-up call into action to protect that little which has remained from the old industrial city that definitely has a very unique spirit. ‘In factories we trust!’

Written by: Juro Sikora

Images by: Juro Sikora and Peter Chrenka